It was the decade when...

Boarding school never looked so good.

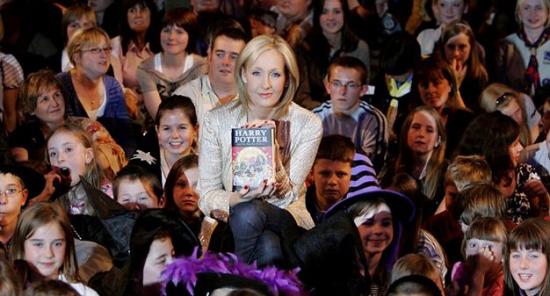

Harry Potter was the Aughts' biggest franchise, a series of books (and later movies) that cast a spell not merely on children but the whole of civil society. To call them "childrens books" is akin to calling the Atlantic Ocean a really big lake. Grown men and women showed no qualms when reading the books in public, often on on park benches and on subway trains, all but advertising their devotion to the series. J.K. Rowling could do no wrong. It wasn't kosher amongst even the most pretentious of the intelligentsia to sneer at the books the way the same crowd did (and should have) for the two other publishing bombshells of the decade, The Da Vinci Code and Twilight. Take that same superior attitude toward the Potter books and you were likely to lose friends fast. Rowling's creation was critic proof, despite whatever Harold Bloom says.

By the time the door-stopper of a final Harry Potter book came out, the release was greeted with the kind of promotional roll-out usually reserved for Michael Bay films or Olympic ceremonies. Deep queues of people dressed as Hufflepuffs and Slytherins waited for hours outside bookstores to grab their midnight copy of Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows, which, after their persistence and patience, they proceeded to read until completion in the wee small hours of the morning. No book can, or maybe ever will, receive such a mardi-gras of celebration upon release. When the smoke had cleared, the series had sold over 400 Million copies and had been translated into over 67 languages. Rowling, who had once subsisted on the government's dole, heads into the next decade a billionaire.

The trick of Harry Potter was Rowling's employment of a traditional coming-of-age narrative filtered through enchanted cheesecloth, creating a "magic" world that was, in fact, analogous to our own. Hogwarts was in most important respects like any boarding school, except at Hogwarts one could converse with the portraiture or learn how to brew aphrodisiacs in chemistry class. Though the muggle (that's Potterian for non-wizard) world seemed anemic and bland next to the Hogwarts fairly-tale, look deeper and its clear that each was but a reflection of the other. All the magic in Harry Potter can be read as a parody of more mundane realities. Even Quidditch, the most popular sport no one has ever played, is little more than an elaborate game of soccer (excuse me, football) taken into the third dimension.

Rowling's myth-making was not the genesis-like creation of an entirely new imaginative eco-system, as was the case with fantasy classics by Tolkien and (dare, I say) George Lucas. Rather than inventing her menagerie of enchanted fauna from thin air, Rowling's potpourri of character types are a grand buffet of mythic creatures and traditional Christian and pagan bogeymen: Wizards and witches, dragons and trolls, giants and werewolves. Rowling was churning through the entire back-catalog of childhood fantasy to make her epic. But, underneath the spells and sorcery were adolescent realities: schoolwork, puberty, nascent sexuality, and the tenuousness of innocence and youth.

The Potter phenomenon did not begin in the Aughts (the first book was published in 1997), but it was the release of the first Harry Potter film, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, in 2001, that kicked off Potter's march toward total cultural dominance. The following series of films based on the books have too been wildly successful in their medium. How successful? Well, all six of the films made so far are among the top 25-highest grossing movies of all time. That successful. And, for the most part, they have achieved artistic as well as commercial success. Though the first two films reek of a heavy-handed and antiseptic Hollywood aesthetic (the blame mainly falling on the director Chris Columbus' less-than-subtle approach), as the series pressed onwards Warner Bros. hired adventuresome and sophisticated directors, supplying greater depth and melancholy to the story. Alfonso Cuaron, Mike Newell, and David Yates have all sat at the director's chair, bringing their dinstictive styles to the property.

For the adults in the room the real joy comes from watching the entire payroll of the Royal Shakespeare Company gnaw at the expensive, stony scenery the way only a British thespian can. Has Alan Rickman, an actor with 16 variations of a sneer, ever been put to better use than in the role of Severus Snape? Could Ralph Fiennes be any more ominous and serpent-like as the Dark Lord Voldemort? And how genius is Maggie Smith as McGonagall, pursuing her lips with the hilariously submerged indignation and hysteria that only the two time Academy Award winner can summon? Or consider Emma Thompson as a batty "divination" instructor? Or Kenneth Branagh as...well, the list goes on. The brilliant cast is the series' secret weapon: not only are they all impeccable in their roles, they're English as Fish & Chips. An cast chock full of Sirs and Dames supplies a national authenticity (the Potter stories, for all their universal appeal, are as British as Brideshead Revisited or Coleman's Mustard) to a production as Hollywood generated and financed as a Transformers film.

When the final installment (halved into two films, lest the cow be anything but totally dry upon final milking) hits multiplexes starting next year, it will be the final curtain to Potters hegemonic dominance on childrens fantasy entertainment. Rowling, the most profitable writer in history, now finds herself with an impossible act to follow. Maybe she'll just spend the rest of her life dropping scandalous morsels of gossip about the characters from her books. Sure, we now know Dumbledore's a homo, but maybe Ms. McGonagall was actually a 60's radical. Or perhaps Ron grows up to become an S&M fetishist. The possibilities are endless. Meanwhile, the books will remain staples of a child's literary diet, easily on a mantle next to the best of Lewis Carrol or C.S. Lewis. Personally, I would like Rowling to keep telling Harry's story. He grew up with us, shouldn't he grow old with us too? Who wouldn't want to read Harry Potter and the Irreversible Herpes Spell? Or Harry Potter and the Cursed Marriage of Doom? And finally, we can't forget Harry Potter and Potter and the Mage's Magic Adult Diaper.

You AUGHT to remember...

Men and women "showed" no qualms. :)

ReplyDeleteThanks. Fixed.

ReplyDelete